Carnavalizar: Method and Invention

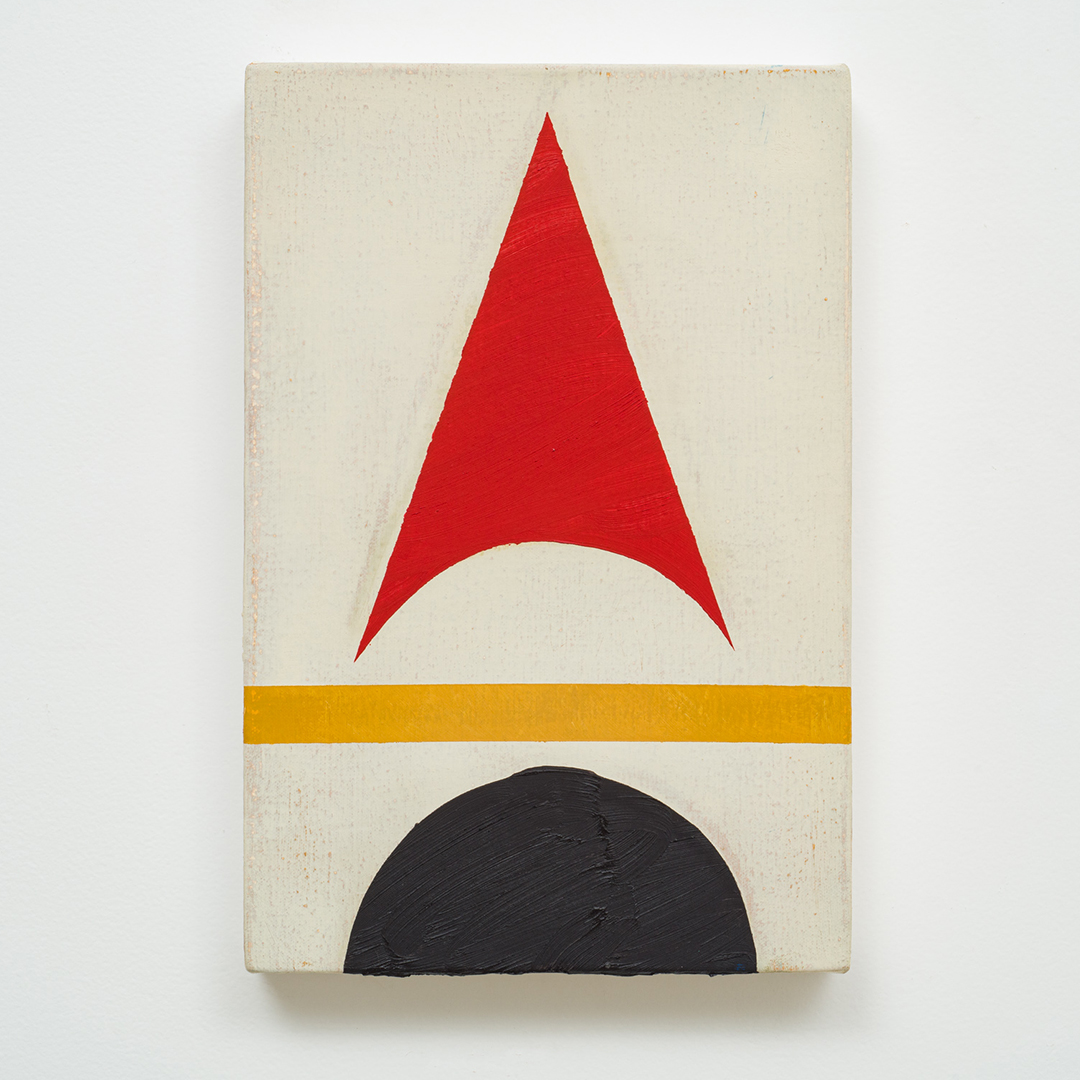

Instead of starting from the noun “carnival”, this exhibition chooses the verb. Carnavalizar [to carnivalize], in Brazil, is a gesture endowed with method: an inventive practice tied to presence, improvisation, and joy in its most radical sense. Moving away from a documentary perspective, the exhibition proposes an almost abstract carnival, elaborating instead a repertoire of states and actions that may relate, directly or indirectly, to the elements of the festivity.

According to historiography, carnival arrives in Brazil imported from Europe and stabilizes into a form close to what we know today after the Paraguayan War, around 1870. Its more distant antecedents go back to festivities dedicated to Dionysus, the Greek god of theater and joy. In the fifteenth century, the Catholic Church incorporated such celebrations into its liturgy. The first transfiguration occurs through flower processions in Spain, masked balls in France and Italy, and the establishment of Christian dates for the event. In Portugal, another modality is added — playful and energetic festivities — which arrive in colonial Brazil.

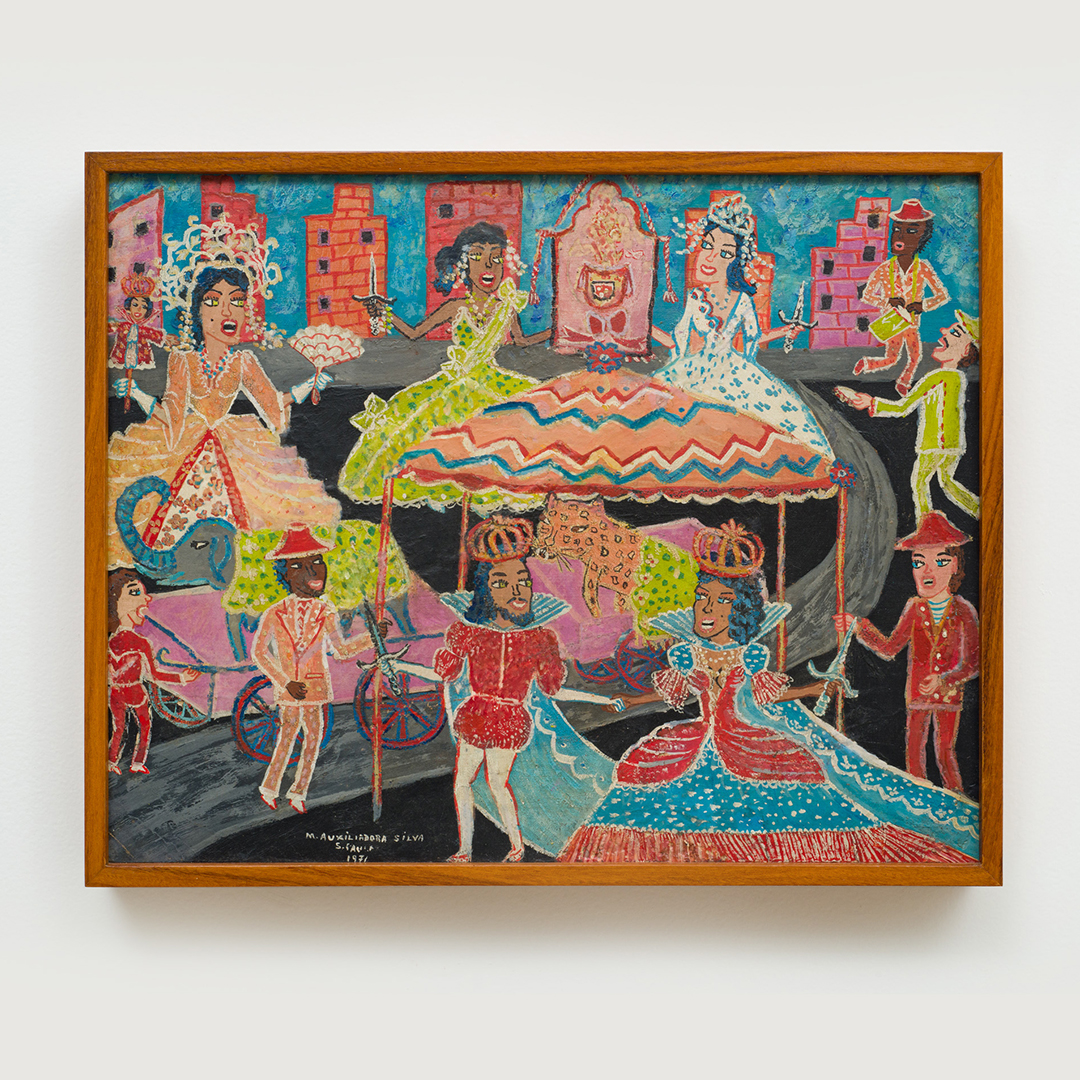

For three centuries, this type of celebration was practiced in the country, until, in the nineteenth century, the Portuguese court imposed a “civilized” carnival, with carriage parades and imported masked balls. At the beginning of the twentieth century, however, a decisive shift emerged from the popular classes, especially from urban Black communities. As Lélia Gonzalez emphasizes, Afro-diasporic peoples recognized carnival as a possible space to reconstruct cultural references obliterated by slavery. The response to colonial violence through carnival was, according to the author, a “double adjustment”: safeguarding African values while inventing a new language. In this movement, the European carnival dissolves and recomposes itself—the Christian legacy is reworked through vigorous rhythms.

Samba Schools, structured in Rio de Janeiro in the late 1920s, are the most striking example: organizations forged in the hills and suburbs, where urban samba asserts itself as a collective and insurgent expression, while also cultivating a deeply communal dimension. In parallel, countless forms of invention flourish: the bate-bolas of Rio’s suburbs, with their exuberant costumes and streets transformed into arenas of play; the maracatus and frevo clubs of Pernambuco, whose choreographies blend African, Indigenous, and European matrices; the afoxés and Afro blocks of Bahia, which since the 1970s have explicitly claimed a re-Africanization of the festival through groups such as Ilê Aiyê and Olodum. In every corner of the country, carnival takes on its own features, sustained by a shared inventive drive.

As Luiz Antonio Simas reminds us, the carnival that prevailed was not the one of elite salons, but that of the streets, of Black communities that, in the post-abolition period, affirmed a way of being together that refused disciplining normativity. In the act of carnavalizar, we can identify a kind of manifesto: the defense of a possible Brazil — diverse, solidaristic, inventive. Thus, as Simas says, it was not we who invented carnival; it was carnival that invented an idea of Brazil that may only fully exist when the country allows itself to carnavalizar.

This exhibition presents works that engage with this verb, thinking of it as both a method and an inventive force, moving across different times to remind us that to carnavalizar has always been more than to celebrate: it is to reorganize space, body, rhythm, and everyday life through a sophisticated popular intelligence. This intelligence also manifests in the vernacular architectures present here, whose principles resonate with the modes activated by the festivity. Improvised construction that becomes structure, the organic quality of interiors, the movement between inside and outside — everything finds resonance in the spatialities created by carnival.

By bringing together artists from different generations, the exhibition allows multiple temporalities, references, and repertoires to coexist, ranging from reflections on the collective body to investigations of the material conditions that sustain both the festivity and life in urban peripheries. In the work of Hélio Oiticica, for example, his experience with Mangueira and the community intelligence of Samba Schools was decisive for the development of the parangolés. The exhibition also expands the understanding that carnival is not limited to samba. The festivity is traversed by a constellation of Afro-diasporic soundings: pulses that intertwine with funk, hip-hop, and the electronic basslines of contemporary street parties.

At the center of all this lies the dimension of assombro [astonishment] evoked by Simas: a mode of perception that allows one to be astonished by the everyday, that recognizes beauty in chance encounters, in a voice that bursts into the street, in a Samba School entering the avenue as if opening up a world. It is a sense of wonder akin to what Cameroonian curator Bonaventure Ndikung identifies in art when he states that, even amid violence, people sing and dance because this restores their certainty that they are still alive. Celebration, in this sense, is a Brazilian technology for dispelling sadness.

By bringing together works that engage with these layers, the exhibition asserts that carnavalizar is a form of knowledge. A method that reorganizes the sensible, breaks down dichotomies, re-scales the collective, and projects futures. Here, different historical times converge to remind us that celebration has never been dissociated from struggle—and that struggle without celebration loses its vitality. Carnavalizar, therefore, is an insistence that politics and poetics can move together, and that this may be the most radical gesture art can offer.

— Daniela Avellar